Perhaps you grew up loving fairy tales, where the beautiful princess ends up living happily ever after with a handsome prince. Maybe you watch rom-coms where the guy and girl end up together despite impossible odds. Maybe you’re addicted to The Bachelor or The Bachelorette and what happens to the lucky couples. When love stories end predictably, how does that make you feel? How do you feel when they end unpredictably, like last year’s La La Land?

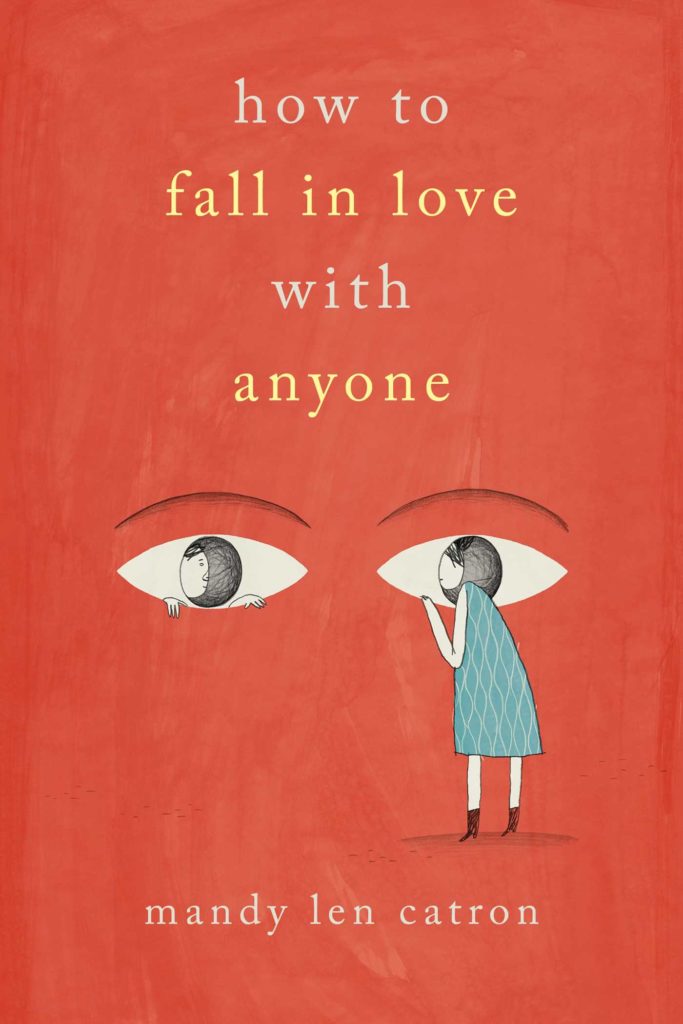

Maybe you’ve never thought much about it. Mandy Len Catron has. The English professor at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, B.C., loves love stories. Throughout her life, she especially loved the love story of her parents, a meet cute between the new football coach and a cheerleader asked to interview him for the school newspaper. So when they divorced after three decades of marriage, when Catron was 26, she began to look deeper into her own nearly decade-long relationship, which was faltering, and what she thought she knew about love. In 2015, she wrote a Modern Love essay for The New York Times, “To Fall in Love With Anyone, Do This” — one of the most-read of the series — and now has a just-released book, How to Fall in Love With Anyone, part-memoir, part exploration about the love stories that we absorb and perhaps allow to dictate our ideas of what love “looks like.”

As she writes in her charming and engaging book:

For most of my life, I’d conceptualized love as something that happened to me. It isn’t merely the stories we tell about love that encourage this attitude, but the very words themselves. In love, we fall. We are struck, we are crushed. We swoon. We burn with passion. Love makes us crazy or it makes us sick. Our hearts ache and then they break. I wondered if this was how love had to work — or if I could take back some control. Science suggested that I could.

One thing she noticed when her Modern Love story, based on research by psychologist Arthur Aron, went viral was that people were eager to discover a “secret” to finding love:

[W]e prefer the short version of the story. My Modern Love column had become an oversimplified romantic fable suggesting there was an ideal way to experience love. It made love predictable, like a script you could follow.

Even Catron didn’t come to love her current partner until months after they tried Aron’s research themselves, when they’d gotten to know each other better. (As an aside, Catron and her partner used the questions posed in The New I Do to create a cohabitation contract that, she writes, “gave us a sense of control” as they merged their lives; Thank you, Mandy!)

Following the love script

We do, of course, have a love script of sorts — meet, date, fall in love, live together, marry, buy a house, have kids. It’s an outdated script; nowadays, many couples have kids first, or buy a house first while living together or apart, or never marry, or never have kids. The romantic script isn’t guiding us so well anymore — and that’s not necessarily a bad thing. The problem is, as Catron beautifully explores in her book, we still buy into it. Our view of love is limited, something that her fellow UBC professor Carrie Jenkins explores in her book, What Love Is and What It Can Be.

In a recent Glamour article, Catron observes that, if we are going to continue to look to love stories to inform us, well, we’d better have access to better, more expansive and more diverse love stories.

What I wish I had as a teenager — and what I think we need more of in the world — are stories that avoid fetishizing love and attempt to reckon with it more honestly. Stories that widen our sense of what’s possible when you offer yourself to another person.

Yes!

I’ve not been as enamored with love stories as Catron has. Sure, I grew up with Disney fairy tales but I also grew up deeply influenced by the 1960s and the free-loving hippie culture. My parents’ love story, such as it was, didn’t seem all that romantic to me as a young girl: my dad’s sister ran into my mom in the elevator of a Bronx apartment, asked if she was single (she was) and told her she should meet her brother. She did, and six months later they married. It wasn’t until many years later, after my mom had died and my dad was in a nursing home and I was cleaning out their condo that I found letters written by men to my mom, responses to an ad her uncle had no doubt placed, looking for a husband for her. She was 19 at the time and an orphan, a Holocaust survivor with limited schooling and skills, an immigrant who most likely needed a husband because she couldn’t live with her aunt and uncle forever. It’s also when I found sweet love poems my father had written to her, acknowledging her “sad eyes.” But by then, I knew the reality of their love story — it was more complicated than romantic.

It’s true that I was the kind of gal who always had a boyfriend around and that the traditional love script was the only one I knew. But now, after I married and divorced twice, and have a pretty full life — financial security (more or less), a house, kids, a career, a group of amazing gal pals I call the Lovelies and on whom I can depend — the traditional love script seems unnecessary. Live together? Marry? Buy a house together? What for?

No guarantees

The gift, if we can call it that, of getting divorced after X-number of years of marriage is that it often makes us question the script that we put so much faith and hope into when we’re just trying to figure love out. Again, that’s not a bad thing; why wouldn’t we want to question it? But it’s not encouraged or even suggested when we’re young and thinking about romantic love and marriage — we often don’t understand that we have choices and there’s no right or wrong choice as long as we’re making it consciously. And that’s the problem. As Catron writes of her parents’ divorce:

Divorce was the wrong ending, one I hadn’t even considered possible. For so long I thought of romantic love as a virtue, a moral triumph, a reward for people who made good life choices. But my parents’ divorce suggested that there were no guarantees in love, not even for the best and most devoted among us, or those of us with the perfect story.

How true! There are no guarantees in love — or anything else, I might add, besides the proverbial cliche — taxes and death — so you can forget about divorce- or affair-proofing a marriage. You can’t. Just be kind, generous and loving, and hope for the best.

Still, Catron suggests we’d all be better off if our love stories weren’t so narrow and constricted. Not to say that we have to be relationship anarchists and make all relationships equal. But we might want to at least tell stories and show models of love that don’t look so predictable, that speak more to the way we actually live and love instead of some idealized and often unsatisfying or unsustainable version of it, stories that recognize that loving relationships are as varied and beautifully complicated as we humans are.

Which is why what Catron writes resonates with me more than anything lately:

Sometimes I wonder if I would’ve loved differently if I’d had more stories like these. If our love stories tell us how a life can go, it would’ve been nice to have had a few more scripts to draw from. Maybe then I would’ve spent less time worrying if I was doing love right and more time thinking about what exactly I wanted from my experience. In fact, I wonder what the world would be like if we all consumed more nuanced, diverse stories of love. Maybe we would stop thinking about love as something that happens to us, and start thinking about it as something we get to offer another person, thoughtfully and with generosity. Or maybe we’d just have more interesting stories about what it means to be human.

Well, there’s no way to know. Yes, we may have loved differently — in fact, we most definitely would have loved differently — but it doesn’t necessarily mean it would be better, easier or more fulfilling. But spending more time thinking about what we want from the experience — that’s key.

Imagine what it would be like if we saw love as “something we get to offer another person, thoughtfully and with generosity.” How would that change your view about love?

Want to have a marriage that’s thoughtful? (Of course you do!) Then read The New I Do: Reshaping Marriage for Skeptics, Realists and Rebels (Seal Press). You can support your local indie bookstore or order it on Amazon.

This is terrific stuff. My regret is that I have gotten so old before getting a better grip on my own reality and a better understanding of relationships. I hope these ideas get through to the younger folks and that they see their way clear to get a better understanding of love and all it entails.