It’s your anniversary (Aw.) You buy your spouse a card, a gift, make plans for a special getaway (and if you have kids, you arrange for someone to care for them for the dinner/weekend away) and that should be it — right? Well, it used to be all that was needed. but nowadays you have to take it one step further; you have to profess your love for your spouse on Facebook, and you have to provide photos of your special day and love online because …

Because, well, why? I don’t know.

At the risk of sounding like a social media curmud-

geon, I have a love-hate thing with social media and there are some things I just don’t understand about it. Mostly the way married people feel compelled to present an idealized version of their lives online. Not to say that they aren’t blissfully happy — I sure hope they are. But I think it’s more about the pressure couples feel to present themselves that way.

Our spouses are a reflection of us, and to present ourselves as other than happy isn’t good for our personal “brand.” Facebook is “a place for good news, not the place where you talk about your most vulnerable self,” says psychologist and author Sherry Turkle. “Marriage lies so close to the raw bone of who you are, so I think people need boundaries and privacy to feel a certain integrity to maintain the relationship.”

Still, we are sending out messages about marriage we may not be aware of. Which is why I was intrigued by the findings of researchers who looked into what they consider the “performance of unattainable marital ideals on Facebook.” In examining postings with hastags of #sadwife, #happywife, #sadhusband and #happyhusband, they discovered that — happy or sad — they represent the same thing: the “performance of an ideal spouse where the inconvenience of everyday chores (laundry, dishes, childcare) and stresses (fiances, marital disputes, familial relationships, resentments) are absent from the rose-tinted world of marital performance on Facebook.”

It’s disturbing to think of marriage — or any relationship — in terms of being a “performance,” although it’s true that, married or not, we often put on our “best” selves to influence how others view us. Social media just amps it up, encouraging and rewarding us for it. Still, the way we talk about our romantic relationships is a form of storytelling and that’s powerful, as Mandy Len Catron details beautifully in her book How to Fall In Love With Anyone.

Facebook just takes it to a weird level of storytelling.

Gendered vision of marriage

We all have feels about people who post their every romantic detail online, even if we aren’t necessarily aware of or don’t pay attention to what research has to say about it — they aren’t really all that happy, they’re narcissistic, they’re insecure, they need validation from others, yada, yada, yada.

But the #sadwife, #happywife, #sadhusband and #happyhusband postings reveal more than that — they speak to a very American version of marriage and a very gendered vision of marriage. They speak to how marriage is based in romantic love, how the couple is the basic unit of society and that it’s based on the husband-wife dyad and reinforces whatever gendered notions of being a “good husband” and “good wife” are to attain “the good life.”

The researchers found more hashtag posts related to wives than husbands, which they suggest may be because women feel more pressure to “perform their ‘wifeness’ online.” And what they post seems to reinforce an idealized form of femininity — of commitment, devotion and undying love. Meanwhile, men’s posts reinforce hegemonic norms — they’re stronger, have more power over and are the caretakers/providers of their wives, maintaining the “institutional dominance of men over women.” Their #happyhusband posts almost always are about food … that their wives made for them — again, a gendered construction of marriage that also validates the “way to a man’s heart is through his stomach” stereotype.

Marriage = ‘complete person’

Ultimately, the researchers find that “the performance of marriage on Facebook reifies the traditional narrative of heterosexual marriage, in which the wife is dependent on her husband’s presence and material support; and husbands rely on wives for good food and domestic care.” Rather than seeing that as a constriction, the couples who post on Facebook “depict a home life centered on the marital dyad as the basis of ‘having it all.’ … To be married is to be a complete person.”

Although I often question the need for couples to profess love and gratitude for a spouse online — can’t you say “I love you” or “You’re the best!” to him or her directly and leave the rest of us out of it? — and while I am very aware of how people curate a perfect online presence, I never considered that what people post on Facebook somehow continues to elevate coupledom as being better than, and reinforces gendered notions of what a “good” marriage looks like. That’s a much more disturbing reality than interpreting such posts as a sign of a couple’s unhappiness and insecurity, or feeling jealous that your romantic partnership isn’t as glowingly perfect as everyone else’s.

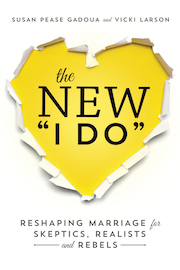

Want to learn how to have a happy marriage by your definition of “happy”? (Of course you do!) Then read The New I Do: Reshaping Marriage for Skeptics, Realists and Rebels (Seal Press). You can support your local indie bookstore or order it on Amazon.